Tag: coupling

Understanding the ID Entanglement Effect

Posted by bsstahl on 2025-02-01 and Filed Under: development

Every developer has faced it: the temptation to make identifiers "smarter" by embedding information. A customer ID that includes their region, an order number containing the date, a product code that encodes its category - these patterns appear innocent at first, even helpful. But they hide a subtle trap I call the "ID Entanglement Effect" - a cascade of complexity that emerges when identifiers become intertwined with business logic and mutable state.

This effect manifests when we blur the line between identification and information, creating a web of dependencies that grows increasingly difficult to maintain. What starts as a convenient shortcut often evolves into a significant source of technical debt, affecting everything from system flexibility to data integrity.

Critical Characteristics

Structural Dependency

Systems relying on a specific format for composite IDs become fragile. Any format change can disrupt functionality and complicate maintenance. For instance, if a system uses "DEPT-EMP-123" as an employee ID, changing the department code structure creates a difficult choice: either update all systems and databases that use this format (a risky and potentially expensive undertaking), or abandon the standard for new records while keeping old IDs in the legacy format. The latter option results in inconsistent IDs across the system where some follow the old standard and others follow the new one, effectively creating a partial, incomplete, and incorrect standard within the IDs themselves. This inconsistency further complicates maintenance and can lead to confusion and errors in data processing.

Data Parsing

When information is embedded in composite IDs, parsing them often appears to be the simplest solution - and it's a completely understandable choice when the data is readily available in the ID itself. Consider an order ID like "2024-01-NA-12345" containing year, region, and sequence number information. Using this embedded data seems more straightforward than querying additional fields or services. However, this parsing must be replicated across different applications and languages, increasing the risk of inconsistencies and errors. The only way to be sure we don't end up parsing these IDs, and in doing so bringing the ID Entanglement Effect into play, is to avoid creating systems that embed business data in identifiers in the first place.

Maintenance Complexity

Parsing logic embedded throughout the codebase increases complexity, making debugging and future development challenging. For example, if an order ID contains both a date and location code (like "20240129-PHX-1234"), every service that processes orders must implement and maintain the same parsing logic. When this logic needs to change, such as adding a new location format, developers must update and test the parsing code across multiple codebases, increasing the risk of inconsistencies.

Inflexibility

Composite IDs limit adaptability. Modifications can ripple through the system, complicating changes or scaling. For example, if a product ID includes a category code (like "TECH-LAPTOP-123"), adding new product categories or reorganizing the category hierarchy becomes a major undertaking. Similarly, if a customer ID includes a region code ("US-WEST-789"), business expansion to new regions or changes in regional organization can require extensive system updates.

Data Integrity Risks

Parsing composite IDs can lead to inconsistencies, especially in dynamic environments. Consider a system where we create product IDs by combining our supplier code with a sequence number (like "SUP123-WIDGET-456"). If the supplier's business is acquired and rebranded, or if the product's manufacturing moves to a different supplier, should all related IDs be updated? This creates significant challenges: either maintain increasingly inaccurate IDs, implement complex ID migration processes, or risk breaking existing references across the system.

Note that using a manufacturer's actual part number (like "ACME-WIDGET-123") as an opaque identifier is perfectly fine - the key is that we treat it as an unchanging reference and don't try to parse meaning from its structure. The ID Entanglement Effect occurs when we create our own composite IDs that encode business relationships or mutable state that we expect to parse and interpret later.

Security Vulnerabilities

Auto-incrementing integers, while simple, introduce significant security risks. Their predictable nature makes it easy for attackers to enumerate resources (like guessing user IDs to access profiles) or gather business intelligence (such as order volumes from sequential order numbers). They can also lead to race conditions in high-concurrency systems and make it difficult to merge data from different sources without ID conflicts.

Long-Term Impact

The ID Entanglement Effect compounds over time, creating increasingly complex challenges:

- Technical Debt: As systems evolve, the cost of maintaining and updating composite ID logic grows exponentially

- Integration Barriers: New systems and third-party integrations must implement complex parsing logic

- Performance Overhead: Constant parsing and validation of composite IDs impacts system performance

- Error Propagation: Mistakes in ID parsing can cascade through multiple systems

- Documentation Burden: Teams must maintain detailed documentation about ID formats and parsing rules

Prevention Strategies

To avoid the ID Entanglement Effect, consider these key strategies:

Use Clean, Stable Identifiers

- Treat all identifiers, especially those from external systems, as opaque strings whose sole purpose is to establish equivalence through exact matching. This is crucial because:

- It prevents accidental coupling to internal structures or business logic that may be embedded in the ID

- It ensures the system remains resilient to changes in ID format or structure

- It maintains compatibility with different ID generation schemes across systems

- It avoids assumptions about ID content that could break when integrating with new systems

- Generate unique identifiers that remain consistent over time

- Human-readable identifiers (like "ORDER-12345") are perfectly acceptable

- Avoid encoding mutable data or business logic in the identifier

- Use non-sequential identifiers (like UUIDs) to prevent enumeration attacks

- Consider the security implications of identifier patterns

Maintain Clear Boundaries

- Store business data in proper fields, not in the identifier

- Keep temporal data (dates, versions) in dedicated attributes

- Track status and metadata independently of the ID

Design for Change

- Assume business rules and categories will evolve

- Plan for system growth and new use cases

- Consider future integration requirements

Best Practices

When designing identifier systems:

- Keep IDs Clean: Use straightforward identifiers that don't encode mutable data

- Separate Concerns: Store business data, status, and metadata in dedicated fields

- Plan for Scale: Choose identifier formats that support future growth

- Consider Relations: Use proper database relationships instead of encoding hierarchies in IDs

- Document Clearly: Maintain clear documentation about identifier generation and usage

Conclusion

The ID Entanglement Effect represents a significant challenge in system design, where the convenience of composite IDs leads to long-term maintenance and scalability issues. By understanding these risks and following best practices for identifier design, teams can create more maintainable and adaptable systems. Remember: while identifiers can be human-readable, they should never become entangled with business logic or mutable state - this separation is key to maintaining system flexibility and reliability over time.

Tags: antipattern architecture coding-practices coupling flexibility

Critical Questions to Ask Your Team About Microservices

Posted by bsstahl on 2023-01-23 and Filed Under: development

Over the last 6 weeks we have discussed the creation, maintenance and operations of microservices and event-driven systems. We explored different conversations that development teams should have prior to working with these types of architectures. Asking the questions we outlined, and answering as many of them as are appropriate, will help teams determine which architectural patterns are best for them, and assist in building their systems and processes in a reliable and supportable way. These conversations are known as "The Critical C's of Microservices", and each is detailed individually in its own article.

The "Critical C's" are: Context, Consistency, Contract, Chaos, Competencies and Coalescence. For easy reference, I have aggregated all of the key elements of each conversation in this article. For details about why each is important, please consult the article specific to that topic.

There is also a Critical C's of Microservices website that includes the same information as in these articles. This site will be kept up-to-date as the guidance evolves.

Questions about Context

Development teams should have conversations around Context that are primarily focused around the tools and techniques that they intend to use to avoid the Dual-Writes Anti-Pattern. These conversations should include answering questions like:

- What database technologies will we use and how can we leverage these tools to create downstream events based on changes to the database state?

- Which of our services are currently idempotent and which ones could reasonably made so? How can we leverage our idempotent services to improve system reliability?

- Do we have any services right now that contain business processes implemented in a less-reliable way? If so, pulling this functionality out into their own microservices might be a good starting point for decomposition.

- What processes will we as a development team implement to track and manage the technical debt of having business processes implemented in a less-reliable way?

- What processes will we implement to be sure that any future less-reliable implementations of business functionality are made with consideration and understanding of the debt being created and a plan to pay it off.

- What processes will we implement to be sure that any existing or future less-reliable implementations of business functionality are documented, understood by, and prioritized by the business process owners.

Questions about Consistency

Development teams should have conversations around Consistency that are primarily focused around making certain that the system is assumed to be eventually consistency throughout. These conversations should include answering questions like:

- What patterns and tools will we use to create systems that support reliable, eventually consistent operations?

- How will we identify existing areas where higher-levels of consistency have been wedged-in and should be removed?

- How will we prevent future demands for higher-levels of consistency, either explicit or assumed, to creep in to our systems?

- How will we identify when there are unusual or unacceptable delays in the system reaching a consistent state?

- How will we communicate the status of the system and any delays in reaching a consistent state to the relevant stakeholders?

Questions about Contract

Development teams should have conversations around Contract that are primarily focused around creating processes that define any integration contracts for both upstream and downstream services, and serve to defend their internal data representations against any external consumers. These conversations should include answering questions like:

- How will we isolate our internal data representations from those of our downstream consumers?

- What types of compatibility guarantees are our tools and practices capable of providing?

- What procedures should we have in place to monitor incoming and outgoing contracts for compatibility?

- What should our procedures look like for making a change to a stream that has downstream consumers?

- How can we leverage upstream messaging contracts to further reduce the coupling of our systems to our upstream dependencies?

Questions about Chaos

Development teams should have conversations around Chaos that are primarily focused around procedures for identifying and remediating possible failure points in the application. These conversations should include answering questions like:

- How will we evaluate potential sources of failures in our systems before they are built?

- How will we handle the inability to reach a dependency such as a database?

- How will we handle duplicate messages sent from our upstream data sources?

- How will we handle messages sent out-of-order from our upstream data sources?

- How will we expose possible sources of failures during any pre-deployment testing?

- How will we expose possible sources of failures in the production environment before they occur for users?

- How will we identify errors that occur for users within production?

- How will we prioritize changes to the system based on the results of these experiments?

Questions about Competencies

Development teams should have conversations around Competencies that are primarily focused around what systems, sub-systems, and components should be built, which should be installed off-the-shelf, and what libraries or infrastructure capabilities should be utilized. These conversations should include answering questions like:

- What are our core competencies?

- How do we identify "build vs. buy" opportunities?

- How do we make "build vs. buy" decisions on needed systems?

- How do we identify cross-cutting concerns and infrastructure capabilites that can be leveraged?

- How do we determine which libraries or infrastructure components will be utilized?

- How do we manage the versioning of utilized components, especially in regard to security updates?

- How do we document our decisions for later review?

Questions about Coalescence

Development teams should have conversations around Coalescence that are primarily focused around brining critical information about the operation of our systems together for easy access. These conversations should include answering questions like:

- What is our mechanism for deployment and system verification?

- How will we identify, as quickly as possible, when a deployment has had a negative impact on our system?

- Are there tests that can validate the operation of the system end-to-end?

- How will we surface the status of any deployment and system verification tests?

- What is our mechanism for logging/traceability within our system?

- How will we coalesce our logs from the various services within the system?

- How will we know if there are anomalies in our logs?

- Are there additional identifiers we need to add to allow traceability?

- Are there log queries that, if enabled, might provide additional support during an outage?

- Are there ways to increase the level of logging when needed to provide additional information and can this be done wholistically on the system?

- How will we expose SLIs and other metrics so they are available when needed?

- How will we know when there are anomalies in our metrics?

- What are the metrics that would be needed in an outage and how will we surface those for easy access?

- Are there additional metrics that, if enabled, might provide additional support during an outage?

- Are there ways to perform ad-hoc queries against SLIs and metrics to provide additional insight in an outage?

- How will we identify the status of dependencies so we can understand when our systems are reacting to downstream anomalies?

- How will we surface dependency status for easy access during an outage?

- Are there metrics we can surface for our dependencies that might help during an outage?

Tags: agile antipattern apache-kafka api apps architecture aspdotnet ci_cd coding-practices coupling event-driven microservices soa

The Critical C's of Microservices - Coalescence

Posted by bsstahl on 2023-01-16 and Filed Under: development

"The Critical C's of Microservices" are a series of conversations that development teams should have around building event-driven or other microservice based architectures. These topics will help teams determine which architectural patterns are best for them, and assist in building their systems and processes in a reliable and supportable way.

The "Critical C's" are: Context, Consistency, Contract, Chaos, Competencies and Coalescence. Each of these topics has been covered in detail in this series of 6 articles. The first article of the 6 was on the subject of Context. This is the final article in the series, and covers the topic of Coalescence.

Coalescence

The use of Microservices reduces the complexity of our services in many ways, however it also adds complexity when it comes to deployment and operations. More services mean more deployments, even as each of those deployments is smaller and more isolated. Additionally, they can be harder on operations and support teams since there can be many more places to go when you need to find information. Ideally, we would coalesce all of the necessary information to operate and troubleshoot our systems in a single pane-of-glass so that our operations and support engineers don't have to search for information in a crisis.

Deployment and system verification testing can help us identify when there are problems at any point in our system and give us insight into what the problems might be and what caused them. Tests run immediately after any deployment can help identify when a particular deployment has caused a problem so it can be addressed quickly. Likewise, ongoing system verification tests can give early indications of problems irrespective of the cause. Getting information about the results of these tests quickly and easily into the hands of the engineers that can act on them can reduce costs and prevent outages.

Logging and traceability is generally considered a solved problem, so long as it is used effectively. We need to setup our systems to make the best use of our distributed logging systems. This often means adding a correlation identifier alongside various request and causation ids to make it easy to trace requests through the system. We also need to be able to monitor and surface our logs so that unusual activity can be recognized and acted on as quickly as possible.

Service Level Indicators (SLIs) and other metrics can provide key insights into the operations of our systems, even if no unusual activity is seen within our logs. Knowing what operational metrics suggest there might be problems within our systems, and monitoring changes to those metrics for both our services and our dependencies can help identify, troubleshoot and even prevent outages. Surfacing those metrics for easy access can give our support and operations engineers the tools they need to do their jobs effectively.

Goals of the Conversation

Development teams should have conversations around Coalescence that are primarily focused around brining critical information about the operation of our systems together for easy access. These conversations should include answering questions like:

- What is our mechanism for deployment and system verification?

- How will we identify, as quickly as possible, when a deployment has had a negative impact on our system?

- Are there tests that can validate the operation of the system end-to-end?

- How will we surface the status of any deployment and system verification tests?

- What is our mechanism for logging/traceability within our system?

- How will we coalesce our logs from the various services within the system?

- How will we know if there are anomalies in our logs?

- Are there additional identifiers we need to add to allow traceability?

- Are there log queries that, if enabled, might provide additional support during an outage?

- Are there ways to increase the level of logging when needed to provide additional information and can this be done wholistically on the system?

- How will we expose SLIs and other metrics so they are available when needed?

- How will we know when there are anomalies in our metrics?

- What are the metrics that would be needed in an outage and how will we surface those for easy access?

- Are there additional metrics that, if enabled, might provide additional support during an outage?

- Are there ways to perform ad-hoc queries against SLIs and metrics to provide additional insight in an outage?

- How will we identify the status of dependencies so we can understand when our systems are reacting to downstream anomalies?

- How will we surface dependency status for easy access during an outage?

- Are there metrics we can surface for our dependencies that might help during an outage?

Tags: agile antipattern apache-kafka api apps architecture aspdotnet ci_cd coding-practices coupling event-driven microservices soa

The Critical C's of Microservices - Competencies

Posted by bsstahl on 2023-01-09 and Filed Under: development

"The Critical C's of Microservices" are a series of conversations that development teams should have around building event-driven or other microservice based architectures. These topics will help teams determine which architectural patterns are best for them, and assist in building their systems and processes in a reliable and supportable way.

The "Critical C's" are: Context, Consistency, Contract, Chaos, Competencies and Coalescence. Each of these topics will be covered in detail in this series of articles. The first article of the 6 was on the subject of Context. This is article 5 of the series, and covers the topic of Competencies.

Competencies

It is our responsibility as engineers to spend our limited resources on those things that give the companies we are building for a competitive advantage in the market. This means limiting our software builds to areas where we can differentiate that company from others. Not every situation requires us to build a custom solution, and even when we do, there is usually no need for us to build every component of that system.

If the problem we are solving is a common one that many companies deal with, and our solution does not give us a competitive advantage over those other companies, we are probably better off using an off-the-shelf product, whether that is a commercial (COTS) product, or a Free or Open-Source one (FOSS). Software we build should be unique to the company it is being built for, and provide that company with a competitive advantage. There is no need for us to build another Customer Relationship Manager (CRM) or Accounting system since these systems implement solutions to solved problemns that are generally solved in the same way by everyone. We should only build custom solutions if we are doing something that has never been done before or we need to do things in a way that is different from everyone else and can't be done using off-the-shelf systems.

We should also only be building custom software when the problem being solved is part of our company's core competencies. If we are doing this work for a company that builds widgets, it is unlikely, though not impossible, that building a custom solution for getting parts needed to build the widgets will provide that company with a competitive advantage. We are probably better off if we focus our efforts on software to help make the widgets in ways that are better, faster or cheaper.

If our "build vs. buy" decision is to build a custom solution, there are likely to be opportunities within those systems to use pre-existing capabilities rather than writing everything from scratch. For example, many cross-cutting concerns within our applications have libraries that support them very effectively. We should not be coding our own implementations for things like logging, configuration and security. Likewise, there are many capabilities that already exist in our infrastructure that we should take advantage of. Encryption, which is often a capability of the operating system, is one that springs to mind. We should certainly never "roll-our-own" for more complex infrastructure features like Replication or Change Data Capture, but might even want to consider avoiding rebuilding infrastructure capabilities that we more commonly build. An example of this might be if we would typically build a Web API for our systems, we might consider exposing the API's of our backing infrastructure components instead, properly isolated and secured of course, perhaps via an API Management component.

Goals of the Conversation

Development teams should have conversations around Competencies that are primarily focused around what systems, sub-systems, and components should be built, which should be installed off-the-shelf, and what libraries or infrastructure capabilities should be utilized. These conversations should include answering questions like:

- What are our core competencies?

- How do we identify "build vs. buy" opportunities?

- How do we make "build vs. buy" decisions on needed systems?

- How do we identify cross-cutting concerns and infrastructure capabilites that can be leveraged?

- How do we determine which libraries or infrastructure components will be utilized?

- How do we manage the versioning of utilized components, especially in regard to security updates?

- How do we document our decisions for later review?

Next Up - Coalescence

In the final article of this series we will look at Coalescence and how we should work to bring all of the data together for our operations & support engineers.

Tags: agile antipattern apache-kafka api apps architecture aspdotnet ci_cd coding-practices coupling event-driven microservices soa

The Critical C's of Microservices - Chaos

Posted by bsstahl on 2023-01-02 and Filed Under: development

"The Critical C's of Microservices" are a series of conversations that development teams should have around building event-driven or other microservice based architectures. These topics will help teams determine which architectural patterns are best for them, and assist in building their systems and processes in a reliable and supportable way.

The "Critical C's" are: Context, Consistency, Contract, Chaos, Competencies and Coalescence. Each of these topics will be covered in detail in this series of articles. The first article of the 6 was on the subject of Context. This is article 4 of the series, and covers the topic of Chaos.

Chaos

One of the Fallacies of Distributed Computing is that the network is reliable. We should have similarly low expectations for the reliability of all of the infrastructure on which our services depend. Networks will segment, commodity servers and drives will fail, containers and operating systems will become unstable. In other words, our software will have errors during operation, no matter how resilient we attempt to make it. We need to embrace the fact that failures will occur in our software, and will do so at random times and often in unpredictable ways.

If we are to build systems that don't require our constant attention, especially during off-hours, we need to be able to identify what happens when failures occur, and design our systems in ways that will allow them to heal automatically once the problem is corrected.

To start this process, I recommend playing "what-if" games using diagrams of the system. Walk through the components of the system, and how the data flows through it, identifying each place where a failure could occur. Then, in each area where failures could happen, attempt to define the possible failure modes and explore what the impact of those failures might be. This kind of "virtual" Chaos Engineering is certainly no substitute for actual experimentation and testing, but is a good starting point for more in-depth analysis. It also can be very valuable in helping to understand the system and to produce more hardened services in the future.

Thought experiments are useful, but you cannot really know how a system will respond to different types of failures until you have those failures in production. Historically, such "tests" have occurred at random, at the whim of the infrastructure, and usually at the worst possible time. Instead of leaving these things to chance, tools like Chaos Monkey can be used to simulate failures in production, and can be configured to create these failures during times where the appropriate support engineers are available and ready to respond if necessary. This way, we can see if our systems respond as we expect, and more importantly, heal themselves as we expect.

Even if you're not ready to jump into using automated experimentation tools in production just yet, a lot can be learned from using feature-flags and changing service behaviors in a more controlled manner as a starting point. This might involve a flag that can be set to cause an API method to return an error response, either as a hard failure, or during random requests for a period of time. Perhaps a switch could be set to stop a service from picking-up asynchronous messages from a queue or topic. Of course, these flags can only be placed in code we control, so we can't test failures of dependencies like databases and other infrastructure components in this way. For that, we'll need more involved testing methods.

Regardless of how we test our systems, it is important that we do everything we can to build systems that will heal themselves without the need for us to intervene every time a failure occurs. As a result, I highly recommend using asynchronous messaging patterns whenever possible. The asynchrony of these tools allow our services to be "temporally decoupled" from their dependencies. As a result, if a container fails and is restarted by Kubernetes, any message in process is rolled-back onto the queue or topic, and the system can pick right up where it left off.

Goals of the Conversation

Development teams should have conversations around Chaos that are primarily focused around procedures for identifying and remediating possible failure points in the application. These conversations should include answering questions like:

- How will we evaluate potential sources of failures in our systems before they are built?

- How will we handle the inability to reach a dependency such as a database?

- How will we handle duplicate messages sent from our upstream data sources?

- How will we handle messages sent out-of-order from our upstream data sources?

- How will we expose possible sources of failures during any pre-deployment testing?

- How will we expose possible sources of failures in the production environment before they occur for users?

- How will we identify errors that occur for users within production?

- How will we prioritize changes to the system based on the results of these experiments?

Next Up - Competencies

In the next article of this series we will look at Competencies and how we should focus at least as much on what we build as how we build it.

Tags: agile antipattern apache-kafka api apps architecture aspdotnet ci_cd coding-practices coupling event-driven microservices soa

The Critical C's of Microservices - Contract

Posted by bsstahl on 2022-12-26 and Filed Under: development

"The Critical C's of Microservices" are a series of conversations that development teams should have around building event-driven or other microservice based architectures. These topics will help teams determine which architectural patterns are best for them, and assist in building their systems and processes in a reliable and supportable way.

The "Critical C's" are: Context, Consistency, Contract, Chaos, Competencies and Coalescence. Each of these topics will be covered in detail in this series of articles. The first article of the 6 was on the subject of Context. This is article 3 of the series, and covers the topic of Contract.

Contract

Once a message has been defined and agreed to as an integration mechanism, all stakeholders in that integration have legitimate expectations of that message contract. Primarily, these expectations includes the agreed-to level of compatibility of future messages, and what the process will be when the contract needs to change. These guarantees will often be such that messages can add fields as needed, but cannot remove, move, or change the nature of existing fields without significant coordination with the stakeholders. This can have a severe impact on the agility of our dev teams as they try to move fast and iterate with their designs.

In order to keep implementations flexible, there should be an isolation layer between the internal representation (Domain Model) of any message, and the more public representation (Integration Model). This way, the developers can change the internal representation with only limited restrictions, so long as as the message remains transformationally compatible with the integration message, and the transformation is modified as needed so that no change is seen by the integration consumers. The two representations may take different forms, such as one in a database, the other in a Kafka topic. The important thing is that the developers can iterate quickly on the internal representation when they need to.

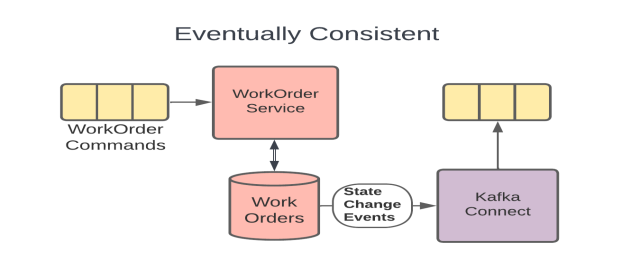

The Eventually Consistent example from the earlier Consistency topic (included above) shows such an isolation layer since the WorkOrders DB holds the internal representation of the message, the Kafka Connect connector is the abstraction that performs the transformation as needed, and the topic that the connector produces data to is the integration path. In this model, the development team can iterate on the model inside the DB without necessarily needing to make changes to the more public Kafka topic.

We need to take great care to defend these internal streams and keep them isolated. Ideally, only 1 service should ever write to our domain model, and only internal services, owned by the same small development team, should read from it. As soon as we allow other teams into our domain model, it becomes an integration model whether we want it to be or not. Even other internal services should use the public representation if it is reasonable to do so.

Similarly, our services should make proper use of upstream integration models. We need to understand what level of compatibility we can expect and how we will be notified of changes. We should use these data paths as much as possible to bring external data locally to our services, in exactly the form that our service needs it in, so that each of our services can own its own data for both reliability and efficiency. Of course, these local stores must be read-only. We need to publish change requests back to the System of Record to make any changes to data sourced by those systems.

We should also do everything we can to avoid making assumptions about data we don't own. Assuming a data type, particular provenance, or embedded-intelligence of a particular upstream data field will often cause problems in the future because we have created unnecessary coupling. As an example, it is good practice to treat all foreign identifiers as strings, even if they look like integers, and to never make assumptions along the lines of "...those identifiers will always be increasing in value". While these may be safe assumptions for a while, they should be avoided if they reasonably can be to prevent future problems.

Goals of the Conversation

Development teams should have conversations around Contract that are primarily focused around creating processes that define any integration contracts for both upstream and downstream services, and serve to defend their internal data representations against any external consumers. These conversations should include answering questions like:

- How will we isolate our internal data representations from those of our downstream consumers?

- What types of compatibility guarantees are our tools and practices capable of providing?

- What procedures should we have in place to monitor incoming and outgoing contracts for compatibility?

- What should our procedures look like for making a change to a stream that has downstream consumers?

- How can we leverage upstream messaging contracts to further reduce the coupling of our systems to our upstream dependencies?

Next Up - Chaos

In the next article of this series we will look at Chaos and how we can use both thought and physical experiments to help improve our system's reliability.

Tags: agile antipattern apache-kafka api apps architecture aspdotnet ci_cd coding-practices coupling event-driven microservices soa

The Critical C's of Microservices - Consistency

Posted by bsstahl on 2022-12-19 and Filed Under: development

"The Critical C's of Microservices" are a series of conversations that development teams should have around building event-driven or other microservice based architectures. These topics will help teams determine which architectural patterns are best for them, and assist in building their systems and processes in a reliable and supportable way.

The "Critical C's" are: Context, Consistency, Contract, Chaos, Competencies and Coalescence. Each of these topics will be covered in detail in this series of articles. Article 1 of the 6 was on the subject of Context. This is article 2 of the series, and covers the topic of Consistency.

Consistency

The world is eventually consistent. The sooner we get that through our heads and start expecting our systems to act like it, the fewer problems, we will have. In fact, I'll go out on a limb and say that most of the problems in building and maintaining microservice architectures are the result of failing to fully embrace eventual consistency from the start.

Data is consistent when it appears the same way when viewed from multiple perspectives. Our systems are said to be consistent when all of the data them is consistent. A system with strong consistency guarantees would be one where every actor, anywhere in the context of the application, would see the exact same value for any data element at any given time. A system that is eventually consistent is one with strong guarantees that the data will reach all intended targets, but much weaker guarantees about how long it might take to achieve data consistency.

Full consistency is impossible in a world where there is a finite speed of causation. Strong consistency can only be achieved when every portion of the application waits until the data is fully consistent before processing. This is generally quite difficult unless all of the data is housed in a single, ACID compliant data store, which of course, is a very bad idea when building scalable systems. Strong consistency, or anything more stringent than eventual consistency, may be appropriate under very specific circumstances when data stores are being geo-replicated (assuming the database server is designed for such a thing), but can cause real difficulties, especially in the areas of reliability and scalability, when attempted inside an application.

We should challenge demands for higher levels of consistency with rigor. Attempts to provide stronger consistency guarantees than eventual will cause far more problems than they are worth.

We will always need to look for situations where consistency problems might occur (i.e. race-conditions), expect them to happen, and try to design our systems in such a way as to not need to worry about them. Race conditions and other consistency problems are smells. If you are in a situation where you are might see these types of problems, it may indicate that you need to reevaluate the details of your implementation.

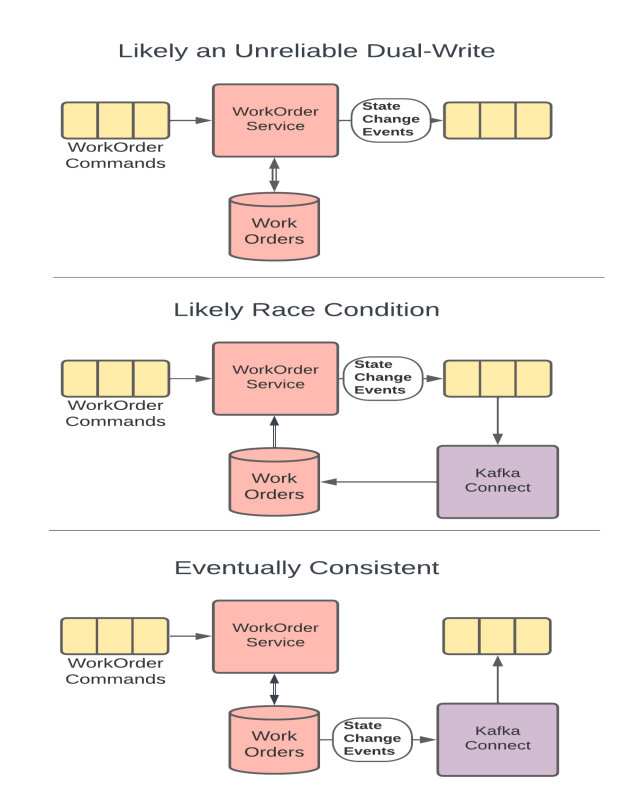

As an example, let's take a look at the 3 implementation diagrams below. In all 3 of these implementations, the goal is to have the WorkOrder service modify a WorkOrder and have the changes published onto a topic for downstream consumers. If a WorkOrder already exists, it needs to be loaded from the data store so that appropriate updates can be made. As you will see, the 3 implementations have very different reliability characteristics.

Implementation 1 - Dual-Write: In the 1st example, the WorkOrder service attempts to both update the entity in the database, and publish the changes to the topic for downstream consumers. This is probably an attempt to keep both the event and the update consistent with one another, and is often mistaken for the simplest solution. However, since it is impossible to make more than 1 reliable change at a time, the only way this implementation can guarantee reliability is if the 1st update is done in an idempotent way. If that is the case, in the circumstances where the 2nd update fails, the service can roll the command message back onto the original topic and try the entire change again. Notice however that this doesn't guarantee consistency at all. If the DB is updated first, it may be done well before the publication ever occurs, since a retry would end up causing the publication to occur on a later attempt. Attempting to be clever and use a DB transaction to maintain consistency actually makes the problem worse for reasons that are outside of the scope of this discussion. Only a distributed transaction across the database and topic would accomplish that, and would do so at the expense of system scalability.

Implementation 2 - Race Condition: In the 2nd example, the WorkOrder service reads data from the DB, and uses that to publish any needed updates to the topic. The topic is then used to feed the database, as well as any additional downstream consumers. While it might seem like the race-condition would be obvious here, it is not uncommon to miss this kind of systemic problem in a more complicated environment. It also can be tempting to build the system this way if the original implementation did not involve the DB. If we are adding the data store, we need to make sure data access happens prior to creating downstream events to avoid this kind of race condition. Stay vigilant for these types of scenarios and be willing to make the changes needed to protect the reliability of your system when requirements change.

Implementation 3 - Eventually Consistent: In the 3rd example, the DB is used directly by both the WorkOrder service, and as the source of changes to the topic. This scenario is reliable but only eventually consistent. That is, we know that both the DB and the topic will be updated since the WorkOrder service makes the DB update directly, and the reliable change feed from the DB instantiates a new execution context for the topic to be updated. This way, there is only a single change to system state made within each execution context, and we can know that they will happen reliably.

Another example of a consistency smell might be when end-users insist that their UI should not return after they update something in an app, until the data is guaranteed to be consistent. I don't blame users for making these requests. After all, we trained them that the way to be sure that a system is reliable is to hit refresh until they see the data. In this situation, assuming we can't talk the users out of it, our best path is to make the UI wait until our polling, or a notification mechanism, identifies that the data is now consistent. I think this is a pretty rude thing to do to our users, but if they insist on it, I can only advise them against it. I will not destroy the scalability of systems I design, and add complexity to these systems that the developers will need to maintain forever, by simulating consistency deeper inside the app. The internals of the application should be considered eventually consistent at all times and we need to get used to thinking about our systems in this way.

Goals of the Conversation

Development teams should have conversations around Consistency that are primarily focused around making certain that the system is assumed to be eventually consistency throughout. These conversations should include answering questions like:

- What patterns and tools will we use to create systems that support reliable, eventually consistent operations?

- How will we identify existing areas where higher-levels of consistency have been wedged-in and should be removed?

- How will we prevent future demands for higher-levels of consistency, either explicit or assumed, to creep in to our systems?

- How will we identify when there are unusual or unacceptable delays in the system reaching a consistent state?

- How will we communicate the status of the system and any delays in reaching a consistent state to the relevant stakeholders?

Next Up - Contract

In the next article of this series we will look at Contract and how we can leverage contracts to make our systems more reliable while still maintaining our agility.

Tags: agile antipattern apache-kafka api apps architecture aspdotnet ci_cd coding-practices coupling event-driven microservices soa

The Critical C's of Microservices - Context

Posted by bsstahl on 2022-12-12 and Filed Under: development

"The Critical C's of Microservices" are a series of conversations that development teams should have around building event-driven or other microservice based architectures. These topics will help teams determine which architectural patterns are best for them, and assist in building their systems and processes in a reliable and supportable way.

The "Critical C's" are: Context, Consistency, Contract, Chaos, Competencies and Coalescence. Each of these topics will be covered in detail in this series of articles, starting with Context.

Update: Part 2 of this series, Consistency is now available.

Context

The Execution Context

The execution context is the unit of work of all services. It represents the life-cycle of a single request, regardless of the details of how that request was received. So, whether an HTTP web request, or an asynchronous message from Apache Kafka or Azure Service Bus, the context we care about here is that of a single service processing that one message. Since, for reasons that will be discussed in a future article, there is no way to reliably make more than one change to system state within a single execution context, we must defend this context from the tendency to add additional state changes which would damage the reliability of our services.

There are generally only two situations where it is ok to make more than one change to system state in a single execution context:

When the first change is idempotent so we can rollback the message and try again later without bad things happening due to duplication. An example of this is a database Upsert where all of the data, including keys, is supplied. In this case, the 1st time we execute the request, we might insert the record in the DB. If a later change fails in the same context and we end up receiving the same message a 2nd time, the resulting update using the same data will leave the system in the same state as if the request was only executed once. Since this idempotent operation can be executed as many times as necessary without impacting the ultimate state of the system, we can make other changes after this one and still rollback and retry the request if a subsequent operation fails, without damaging the system. Services that are idempotent are much easier to orchestrate reliably, so much so that idempotence is considered a highly-desireable feature of microservices.

When the second change is understood to be less-reliable. An example of this is logging. We don't want to fail a business-process due to failures in logging, so we accept that our logging, and certain other technical processes, may be less-reliable than our business processes. It is rarely ok for a business process to be less-reliable in this way. Implementations that make certain business features less-reliable should be identified, documented, and discussed with an eye toward repaying what is likely to be technical debt.

Avoiding Dual-Writes

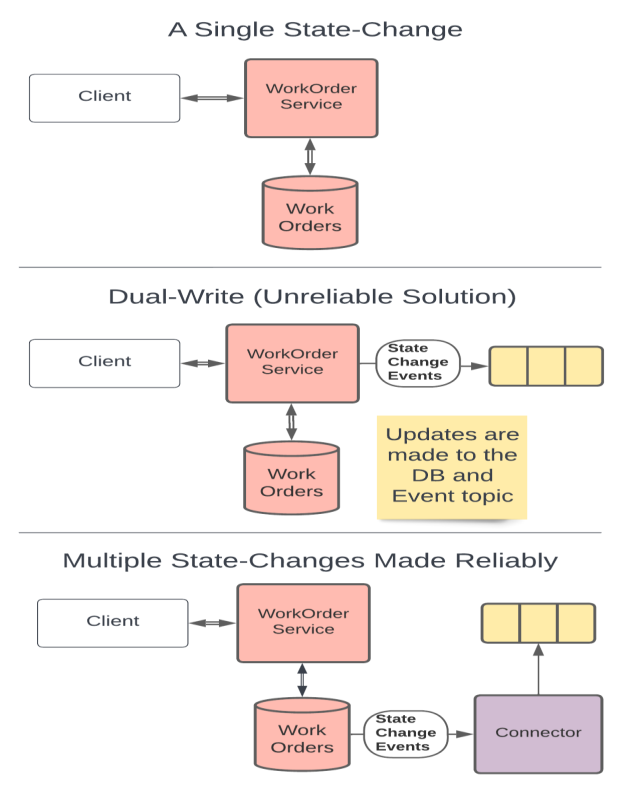

Ultimately, to maintain the reliability of our systems, we must be sure we are never trying to make more than one reliable change to system state in a single execution context. This is a very different way of thinking than most developers are used to. In fact, I would say it is the opposite of how many of us have been taught to think about these types of problems. Developers value simplicity, and rightfully so. Unfortunately, problems where we already have a service running that can host logic we need to add, make it seem like the simplest solution is to just "add-on" the new logic to the existing code. The truth of the matter is far different. Let's look at an example:

In these drawings we start with a RESTful service that updates a database and returns an appropriate response. This service makes only 1 change to system state so it can be built reliably.

The next two drawings show ways of implementing a new requirement for the system to update a downstream dependency, say a Kafka topic, in addition to the database update. The default for many Technologists would be to just to add-on inside the service. That is, they might suggest that we should have the service update both the database and the topic as shown in the second drawing. This would be an example of the Dual-Writes Anti-Pattern and would hurt both system reliability and supportability.

Instead, the simplest solution that doesn't harm our system's reliability is actually to trigger the downstream action off of the DB update. That is, we can use the Outbox Pattern or if the database supports it, Change Data Capture or a Change Feed to trigger a secondary process that produces the event message. Adding a deployment unit like this might make it feel like a more complicated solution, however it actually reduces the complexity of the initial service, avoids making a change to a working service, and will avoid creating reliability problems by not performing dual-writes.

There are a few things to note here regarding atomic database transactions. An ACID-compliant update to a database represents a single change to system state. If we could make fully ACID-compliant changes across multiple data stores, or other boundaries like web services, the Dual-Writes Anti-Pattern would be much less of a problem. Unfortunately, distributed transactions cannot be used without severely impacting both scalability and performance and are not recommended. It should also be noted that, when talking about only 2 state changes, some threats to reliability may be reduced by being clever with our use of transactions. However, these tricks help us far less than one might think, and have severely diminishing returns when 3 or more state-changes are in-scope. Transactions, while good for keeping local data consistent, are not good for maintaining system reliability and are horrible for system scalability.

Goals of the Conversation

Development teams should have conversations around Context that are primarily focused around the tools and techniques that they intend to use to avoid the Dual-Writes Anti-Pattern. These conversations should include answering questions like:

What database technologies will we use and how can we leverage these tools to create downstream events based on changes to the database state?

Which of our services are currently idempotent and which ones could reasonably made so? How can we leverage our idempotent services to improve system reliability?

Do we have any services right now that contain business processes implemented in a less-reliable way? If so, pulling this functionality out into their own microservices might be a good starting point for decomposition.

What processes will we as a development team implement to track and manage the technical debt of having business processes implemented in a less-reliable way?

What processes will we implement to be sure that any future less-reliable implementations of business functionality are made with consideration and understanding of the debt being created and a plan to pay it off.

What processes will we implement to be sure that any existing or future less-reliable implementations of business functionality are documented, understood by, and prioritized by the business process owners.

Next Up - Consistency

In the next article of this series we will look at Consistency, and see how Eventual Consistency represents the reality of the world we live in.

Tags: agile antipattern apache-kafka api apps architecture aspdotnet ci_cd coding-practices coupling event-driven microservices soa

Identifying the Extraneous Publishing AntiPattern

Posted by bsstahl on 2022-08-08 and Filed Under: development

What do you do when a dependency of one of your components needs data, ostensibly from your component, that your component doesn't actually need itself?

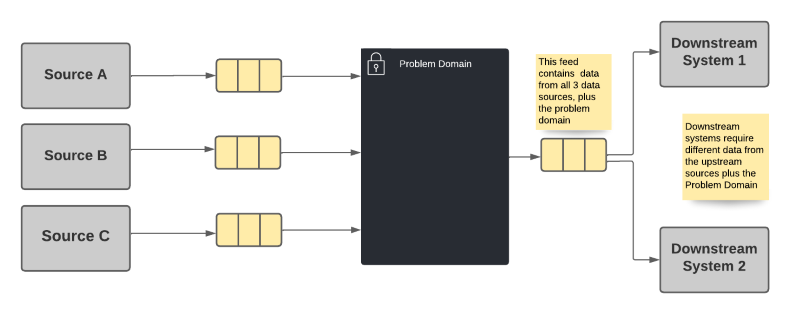

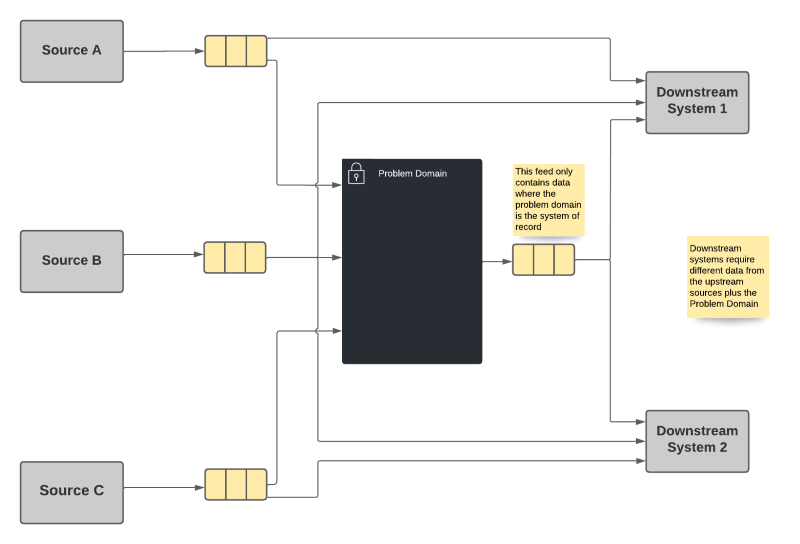

Let's think about an example. Suppose our problem domain (the big black box in the drawings below) uses some data from 3 different data sources (labeled Source A, B & C in the drawings). There is also a downstream dependency that needs data from the problem domain, as well as from sources B & C. Some of the data required by the downstream dependency are not needed by, or owned by, the problem domain.

There are 2 common implementations discussed now, and 1 slightly less obvious one discussed later in this article. We could:

- Pass-through the needed values on the output from our problem domain. This is the default option in many environments.

- Force the downstream to take additional dependencies on sources B & C

Note: In the worst of these cases, the data from one or more of these sources is not needed at all in the problem domain.

Option 1 - Increase Stamp Coupling

The most common choice is for the problem domain to publish all data that it is system of record for, as well as passing-through data needed by the downstream dependencies from the other sources. Since we know that a dependency needs the data, we simply provide it as part of the output of the problem domain system.

Option 1 Advantages

- The downstream systems only needs to take a dependency on a single data source.

Option 1 Disadvantages

- Violates the Single Responsibility Principle because the problem domain may need to change for reasons the system doesn't care about. This can occur if a upstream producer adds or changes data, or a downstream consumer needs additional or changed data.

- The problem domain becomes the de-facto system of record for data it doesn't own. This may cause downstream consumers to be blocked by changes important to the consumers but not the problem domain. It also means that the provenance of the data is obscured from the consumer.

- Problems incurred by upstream data sources are exposed in the problem domain rather than in the dependent systems, irrespective of where the problem occurs or whether that problem actually impacts the problem domain. That is, the owners of the system in the problem domain become the "one neck to wring" for problems with the data, regardless of whether the problem is theirs, or they even care about that data.

I refer to this option as an implementation of the Extraneous Publishing Antipattern (Thanks to John Nusz for the naming suggestion). When this antipattern is used it will eventually cause significant problems for both the problem domain and its consumers as they evolve independently and the needs of each system change. The problem domain will be stuck with both their own requirements, and the requirements of their dependencies. The dependent systems meanwhile will be stuck waiting for changes in the upstream data provider. These changes will have no priority in that system because the changes are not needed in that domain and are not cared about by that product's ownership.

The relationship between two components created by a shared data contract is known as stamp coupling. Like any form of coupling, we should attempt to minimize it as much as possible between components so that we don't create hard dependencies that reduce our agility.

Option 2 - Multiplicative Dependencies

This option requires each downstream system to take a dependency on every system of record whose data it needs, regardless of what upstream data systems may already be utilizing that data source.

Option 2 Advantages

- Each system publishes only that information for which it is system of record, along with any necessary identifiers.

- Each dependency gets its data directly from the system of record without concern for intermediate actors.

Option 2 Disadvantages

- A combinatorial explosion of dependencies is possible since each system has to take dependencies on every system it needs data from. In some cases, this means that the primary systems will have a huge number of dependencies.

While there is nothing inherently wrong with having a large number of repeated dependencies within the broader system, it can still cause difficulties in managing the various products when the dependency graph starts to get unwieldy. We've seen similar problems in package-management and other dependency models before. However, there is a more common problem when we prematurely optimize our systems. If we optimize prematurely, we can create artifacts that we need to support forever, that create unnecessary complexity. As a result, I tend to use option 2 until the number of dependencies starts to grow. At that point, when the dependency graph starts to get out of control, we should look for another alternative.

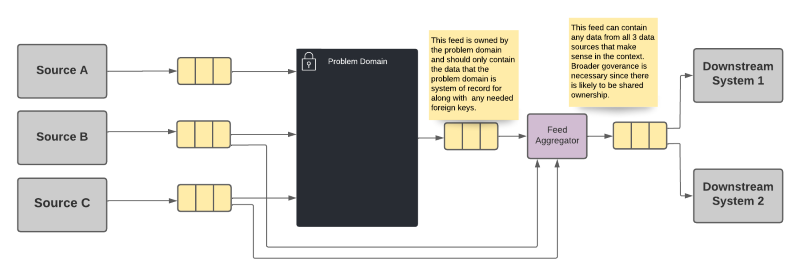

Option 3 - Shared Aggregation Feed

Fortunately, there is a third option that may not be immediately apparent. We can get the best of both worlds, and limit the impact of the disadvantages described above, by moving the aggregation of the data to a separate system. In fact, depending on the technologies used, this aggregation may be able to be done using an infrastructure component that is a low-code solution less likely to have reliability concerns.

In this option, each system publishes only the data for which it is system of record, as in option 1 above. However, instead of every system having to take a direct dependency on all of the upstream systems, a separate component is used to create a shared feed that represents the aggregation of the data from all of the sources.

Option 3 Advantages

- Each system publishes only that information for which it is system of record, along with any necessary identifiers.

- The downstream systems only needs to take a dependency on a single data source.

- A shared ownership can be arranged for the aggregation source that does not put the burden entirely on a single domain team.

Option 3 Disadvantages

- The aggregation becomes the de-facto system of record for data it doesn't own, though that fact is anticipated and hopefully planned for. The ownership of this aggregation needs to be well-defined, potentially even shared among the teams that provide data for the aggregation. This still means though that the provenance of the data is obscured from the consumer.

- Problems incurred by upstream data sources are exposed in the aggregator rather than in the dependent systems, irrespective of where the problem occurs. That is, the owners of the aggregation system become the "one neck to wring" for problems with the data. However, as described above, that ownership can be shared among the teams that own the data sources.

It should be noted that in any case, regardless of implementation, a mechanism for correlating data across the feeds will be required. That is, the entity being described will need either a common identifier, or a way to translate the identifiers from one system to the others so that the system can match the data for the same entities appropriately.

You'll notice that the aggregation system described in this option suffers from some of the same disadvantages as the other two options. The biggest difference however is that the sole purpose of this tool is to provide this aggregation. As a result, we handle all of these drawbacks in a domain that is entirely built for this purpose. Our business services remain focused on our business problems, and we create a special domain for the purpose of this data aggregation, with development processes that serve that purpose. In other words, we avoid expanding the definition of our problem domain to include the data aggregation as well. By maintaining each component's single responsibility in this way, we have the best chance of remaining agile, and not losing velocity due to extraneous concerns like unnecessary data dependencies.

Implementation

There are a number of ways we can perform the aggregation described in option 3. Certain databases such as MongoDb and CosmosDb provide mechanisms that can be used to aggregate multiple data elements. There are also streaming data implementations which include tools for joining multiple streams, such as Apache Kafka's kSQL. In future articles, I will explore some of these methods for minimizing stamp coupling and avoiding the Extraneous Publishing AntiPattern.