The Critical C's of Microservices - Context

Posted by bsstahl on 2022-12-12 and Filed Under: development

"The Critical C's of Microservices" are a series of conversations that development teams should have around building event-driven or other microservice based architectures. These topics will help teams determine which architectural patterns are best for them, and assist in building their systems and processes in a reliable and supportable way.

The "Critical C's" are: Context, Consistency, Contract, Chaos, Competencies and Coalescence. Each of these topics will be covered in detail in this series of articles, starting with Context.

Update: Part 2 of this series, Consistency is now available.

Context

The Execution Context

The execution context is the unit of work of all services. It represents the life-cycle of a single request, regardless of the details of how that request was received. So, whether an HTTP web request, or an asynchronous message from Apache Kafka or Azure Service Bus, the context we care about here is that of a single service processing that one message. Since, for reasons that will be discussed in a future article, there is no way to reliably make more than one change to system state within a single execution context, we must defend this context from the tendency to add additional state changes which would damage the reliability of our services.

There are generally only two situations where it is ok to make more than one change to system state in a single execution context:

When the first change is idempotent so we can rollback the message and try again later without bad things happening due to duplication. An example of this is a database Upsert where all of the data, including keys, is supplied. In this case, the 1st time we execute the request, we might insert the record in the DB. If a later change fails in the same context and we end up receiving the same message a 2nd time, the resulting update using the same data will leave the system in the same state as if the request was only executed once. Since this idempotent operation can be executed as many times as necessary without impacting the ultimate state of the system, we can make other changes after this one and still rollback and retry the request if a subsequent operation fails, without damaging the system. Services that are idempotent are much easier to orchestrate reliably, so much so that idempotence is considered a highly-desireable feature of microservices.

When the second change is understood to be less-reliable. An example of this is logging. We don't want to fail a business-process due to failures in logging, so we accept that our logging, and certain other technical processes, may be less-reliable than our business processes. It is rarely ok for a business process to be less-reliable in this way. Implementations that make certain business features less-reliable should be identified, documented, and discussed with an eye toward repaying what is likely to be technical debt.

Avoiding Dual-Writes

Ultimately, to maintain the reliability of our systems, we must be sure we are never trying to make more than one reliable change to system state in a single execution context. This is a very different way of thinking than most developers are used to. In fact, I would say it is the opposite of how many of us have been taught to think about these types of problems. Developers value simplicity, and rightfully so. Unfortunately, problems where we already have a service running that can host logic we need to add, make it seem like the simplest solution is to just "add-on" the new logic to the existing code. The truth of the matter is far different. Let's look at an example:

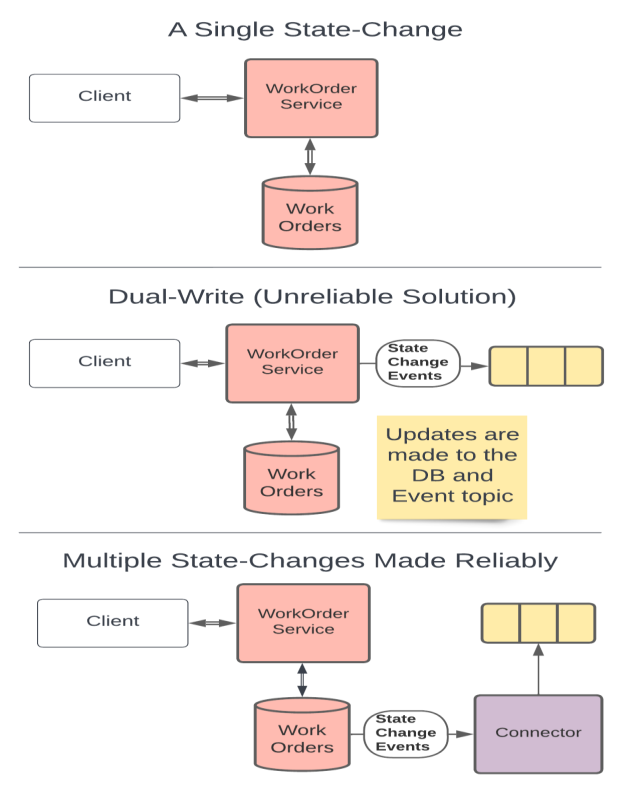

In these drawings we start with a RESTful service that updates a database and returns an appropriate response. This service makes only 1 change to system state so it can be built reliably.

The next two drawings show ways of implementing a new requirement for the system to update a downstream dependency, say a Kafka topic, in addition to the database update. The default for many Technologists would be to just to add-on inside the service. That is, they might suggest that we should have the service update both the database and the topic as shown in the second drawing. This would be an example of the Dual-Writes Anti-Pattern and would hurt both system reliability and supportability.

Instead, the simplest solution that doesn't harm our system's reliability is actually to trigger the downstream action off of the DB update. That is, we can use the Outbox Pattern or if the database supports it, Change Data Capture or a Change Feed to trigger a secondary process that produces the event message. Adding a deployment unit like this might make it feel like a more complicated solution, however it actually reduces the complexity of the initial service, avoids making a change to a working service, and will avoid creating reliability problems by not performing dual-writes.

There are a few things to note here regarding atomic database transactions. An ACID-compliant update to a database represents a single change to system state. If we could make fully ACID-compliant changes across multiple data stores, or other boundaries like web services, the Dual-Writes Anti-Pattern would be much less of a problem. Unfortunately, distributed transactions cannot be used without severely impacting both scalability and performance and are not recommended. It should also be noted that, when talking about only 2 state changes, some threats to reliability may be reduced by being clever with our use of transactions. However, these tricks help us far less than one might think, and have severely diminishing returns when 3 or more state-changes are in-scope. Transactions, while good for keeping local data consistent, are not good for maintaining system reliability and are horrible for system scalability.

Goals of the Conversation

Development teams should have conversations around Context that are primarily focused around the tools and techniques that they intend to use to avoid the Dual-Writes Anti-Pattern. These conversations should include answering questions like:

What database technologies will we use and how can we leverage these tools to create downstream events based on changes to the database state?

Which of our services are currently idempotent and which ones could reasonably made so? How can we leverage our idempotent services to improve system reliability?

Do we have any services right now that contain business processes implemented in a less-reliable way? If so, pulling this functionality out into their own microservices might be a good starting point for decomposition.

What processes will we as a development team implement to track and manage the technical debt of having business processes implemented in a less-reliable way?

What processes will we implement to be sure that any future less-reliable implementations of business functionality are made with consideration and understanding of the debt being created and a plan to pay it off.

What processes will we implement to be sure that any existing or future less-reliable implementations of business functionality are documented, understood by, and prioritized by the business process owners.

Next Up - Consistency

In the next article of this series we will look at Consistency, and see how Eventual Consistency represents the reality of the world we live in.