Tag: ksql

Identifying the Extraneous Publishing AntiPattern

Posted by bsstahl on 2022-08-08 and Filed Under: development

What do you do when a dependency of one of your components needs data, ostensibly from your component, that your component doesn't actually need itself?

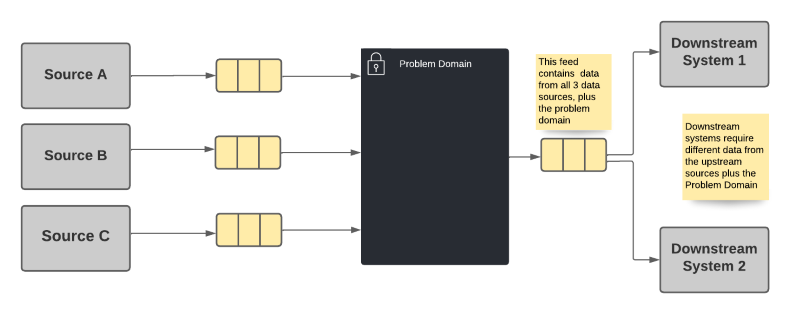

Let's think about an example. Suppose our problem domain (the big black box in the drawings below) uses some data from 3 different data sources (labeled Source A, B & C in the drawings). There is also a downstream dependency that needs data from the problem domain, as well as from sources B & C. Some of the data required by the downstream dependency are not needed by, or owned by, the problem domain.

There are 2 common implementations discussed now, and 1 slightly less obvious one discussed later in this article. We could:

- Pass-through the needed values on the output from our problem domain. This is the default option in many environments.

- Force the downstream to take additional dependencies on sources B & C

Note: In the worst of these cases, the data from one or more of these sources is not needed at all in the problem domain.

Option 1 - Increase Stamp Coupling

The most common choice is for the problem domain to publish all data that it is system of record for, as well as passing-through data needed by the downstream dependencies from the other sources. Since we know that a dependency needs the data, we simply provide it as part of the output of the problem domain system.

Option 1 Advantages

- The downstream systems only needs to take a dependency on a single data source.

Option 1 Disadvantages

- Violates the Single Responsibility Principle because the problem domain may need to change for reasons the system doesn't care about. This can occur if a upstream producer adds or changes data, or a downstream consumer needs additional or changed data.

- The problem domain becomes the de-facto system of record for data it doesn't own. This may cause downstream consumers to be blocked by changes important to the consumers but not the problem domain. It also means that the provenance of the data is obscured from the consumer.

- Problems incurred by upstream data sources are exposed in the problem domain rather than in the dependent systems, irrespective of where the problem occurs or whether that problem actually impacts the problem domain. That is, the owners of the system in the problem domain become the "one neck to wring" for problems with the data, regardless of whether the problem is theirs, or they even care about that data.

I refer to this option as an implementation of the Extraneous Publishing Antipattern (Thanks to John Nusz for the naming suggestion). When this antipattern is used it will eventually cause significant problems for both the problem domain and its consumers as they evolve independently and the needs of each system change. The problem domain will be stuck with both their own requirements, and the requirements of their dependencies. The dependent systems meanwhile will be stuck waiting for changes in the upstream data provider. These changes will have no priority in that system because the changes are not needed in that domain and are not cared about by that product's ownership.

The relationship between two components created by a shared data contract is known as stamp coupling. Like any form of coupling, we should attempt to minimize it as much as possible between components so that we don't create hard dependencies that reduce our agility.

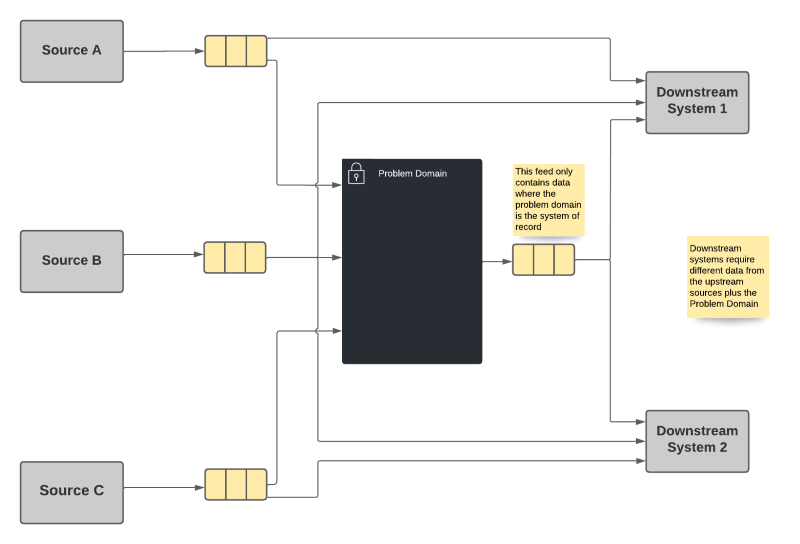

Option 2 - Multiplicative Dependencies

This option requires each downstream system to take a dependency on every system of record whose data it needs, regardless of what upstream data systems may already be utilizing that data source.

Option 2 Advantages

- Each system publishes only that information for which it is system of record, along with any necessary identifiers.

- Each dependency gets its data directly from the system of record without concern for intermediate actors.

Option 2 Disadvantages

- A combinatorial explosion of dependencies is possible since each system has to take dependencies on every system it needs data from. In some cases, this means that the primary systems will have a huge number of dependencies.

While there is nothing inherently wrong with having a large number of repeated dependencies within the broader system, it can still cause difficulties in managing the various products when the dependency graph starts to get unwieldy. We've seen similar problems in package-management and other dependency models before. However, there is a more common problem when we prematurely optimize our systems. If we optimize prematurely, we can create artifacts that we need to support forever, that create unnecessary complexity. As a result, I tend to use option 2 until the number of dependencies starts to grow. At that point, when the dependency graph starts to get out of control, we should look for another alternative.

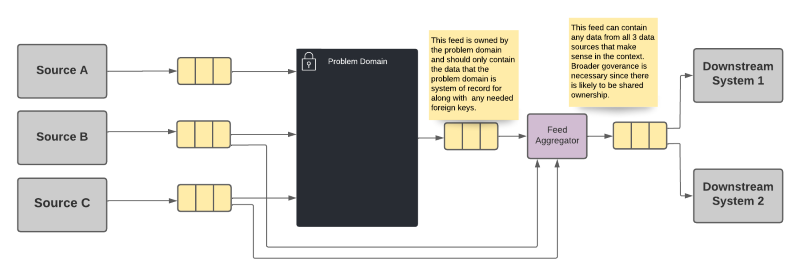

Option 3 - Shared Aggregation Feed

Fortunately, there is a third option that may not be immediately apparent. We can get the best of both worlds, and limit the impact of the disadvantages described above, by moving the aggregation of the data to a separate system. In fact, depending on the technologies used, this aggregation may be able to be done using an infrastructure component that is a low-code solution less likely to have reliability concerns.

In this option, each system publishes only the data for which it is system of record, as in option 1 above. However, instead of every system having to take a direct dependency on all of the upstream systems, a separate component is used to create a shared feed that represents the aggregation of the data from all of the sources.

Option 3 Advantages

- Each system publishes only that information for which it is system of record, along with any necessary identifiers.

- The downstream systems only needs to take a dependency on a single data source.

- A shared ownership can be arranged for the aggregation source that does not put the burden entirely on a single domain team.

Option 3 Disadvantages

- The aggregation becomes the de-facto system of record for data it doesn't own, though that fact is anticipated and hopefully planned for. The ownership of this aggregation needs to be well-defined, potentially even shared among the teams that provide data for the aggregation. This still means though that the provenance of the data is obscured from the consumer.

- Problems incurred by upstream data sources are exposed in the aggregator rather than in the dependent systems, irrespective of where the problem occurs. That is, the owners of the aggregation system become the "one neck to wring" for problems with the data. However, as described above, that ownership can be shared among the teams that own the data sources.

It should be noted that in any case, regardless of implementation, a mechanism for correlating data across the feeds will be required. That is, the entity being described will need either a common identifier, or a way to translate the identifiers from one system to the others so that the system can match the data for the same entities appropriately.

You'll notice that the aggregation system described in this option suffers from some of the same disadvantages as the other two options. The biggest difference however is that the sole purpose of this tool is to provide this aggregation. As a result, we handle all of these drawbacks in a domain that is entirely built for this purpose. Our business services remain focused on our business problems, and we create a special domain for the purpose of this data aggregation, with development processes that serve that purpose. In other words, we avoid expanding the definition of our problem domain to include the data aggregation as well. By maintaining each component's single responsibility in this way, we have the best chance of remaining agile, and not losing velocity due to extraneous concerns like unnecessary data dependencies.

Implementation

There are a number of ways we can perform the aggregation described in option 3. Certain databases such as MongoDb and CosmosDb provide mechanisms that can be used to aggregate multiple data elements. There are also streaming data implementations which include tools for joining multiple streams, such as Apache Kafka's kSQL. In future articles, I will explore some of these methods for minimizing stamp coupling and avoiding the Extraneous Publishing AntiPattern.