Tag: solid

Testing the Untestable with Microsoft Fakes

Posted by bsstahl on 2017-03-20 and Filed Under: development

It is fairly easy these days to test code in isolation if its dependencies are abstracted by a reusable interface. But what do we do if the dependency cannot easily be referenced via such an interface? Enter Shims, from the Microsoft Fakes Framework(formerly Moles). Shims allow us to isolate our testing from any dependent methods, including methods in assemblies we do not control, even if those methods are not exposed through a reusable interface. To see how easy it is, follow along with me through this example.

In this sample code on GitHub, we are building a repository for an application that currently gets its data from a file exported from a system that tracks scheduled meetings. It is very likely that the system will, in the future, expose a more modern interface for that data so we have isolated the data storage using a simple Repository interface that has one method. This method, called GetMeetings returns a collection of Meeting entities that start during the specified date range. The method will return an empty collection if no data is found matching the specified criteria, and could throw either of 2 custom errors, a PermissionsExceptionwhen the user does not have the proper permissions to access the information, and a DataUnavailableException for when the data source is unavailable for any other reason, such as a network outage or if the data file cannot be located.

It is important to point out why a custom exception should be thrown when the data file is not found, rather than allowing the FileNotFoundException to bubble-up. If we allow the implementation-specific exception to bubble, we have exposed an implementation detail to the caller. That is, the calling code is now aware of the fact that this is a file system implementation. If code is written in a client that traps for FileNotFoundException, then the repository implementation is swapped-out for a SQL server implementation, the client code will have to change to handle the new types of errors that could be thrown by that implementation. This violates the Dependency Inversion principle, the “D” from the SOLID principles. By exposing only a custom exception, we are hiding those implementation details from the caller.

Downstream clients can easily test code that uses this repository without having to actually access the repository implementation because we have exposed the IMeetingSourceRepository interface. However, it is a bit more difficult to actually test the repository implementation itself. We have a few options here:

- Create data files that hold known data samples and load those files during unit testing.

- Create a wrapper around the System.IO namespace that exposes an interface, such as in the System.IO.Abstractions project.

- Don’t test any code that requires reaching-out to the file system.

Since I am of the opinion that 100% code coverage is both reasonable, and desirable (although not a measurable goal), I will summarily dispose of option 3 for the purpose of this analysis. I have used option 2 many times in my life, and while employing wrapper code is a valid and reasonable solution, it adds additional code to my production deployments that is very limited in terms of what it adds to the loose-coupling of my solution since I already am loosely-coupled to this implementation via the IMeetingSourceRepository interface.

Even though it is far from a perfect solution (many would consider them more integration tests than unit tests), I initially selected option 1 for this implementation. That is, I created data files and deployed them along with my tests. You can see the test files I created in the Data folder of the MeetingSystem.Data.FileSystem.Test project. These files are deployed alongside my tests using the DeploymentItem directive that decorates the Repository_GetMeetings_Should class of the test project. Using this method, I was able to create tests that:

- Verify that the correct # of meetings are returned from a file

- Verify that meetings are properly filtered by the StartDateTime of the meeting

- Validate the data elements returned from the file

- Validate that the proper custom exception is thrown if a FileNotFoundException is thrown by the underlying code

So we have verified nearly everything we need to test in our implementation. We’ve verified that the data is returned properly, and that one of our custom exceptions is being returned. But what about the PermissionsException? We were able to simulate a FileNotFoundException in our tests by just using a bad filename, but how do we test for a permissions problem? The ReadAllText method of the File object from System.IO will throw a System.Security.SecurityException if the file cannot be read due to a permissions problem. We need to trap this exception and throw our own exception, but how can we validate that we have successfully done so and that the functionality remains intact through future refactoring? How can we simulate a permissions exception on a file that we have enough permission on to deploy to a test folder? Enter Shims from the Microsoft Fakes Framework.

Instead of having our tests actually reach-out to the file system and actually try to load a file, we can intercept calls to the System.IO.File.ReadAllText method and have those calls execute some delegate code instead. This code, which we write in our test methods, can be specific to each test and exist only within the context of the test. As a result, we are not deploying any additional code to production, while still thoroughly validating our code. In fact, using this methodology, I could re-implement my previous tests, including my test data in the tests themselves, making these tests better unit tests. I could then reserve tests that actually reach out to files for integration test libraries that are run less frequently, and perhaps even behind the scenes.

Note: If you wish to follow-along with these instructions, you can grab the code from the DemoStart branch of the GitHub repo, rather than the Master branch where this is already done.

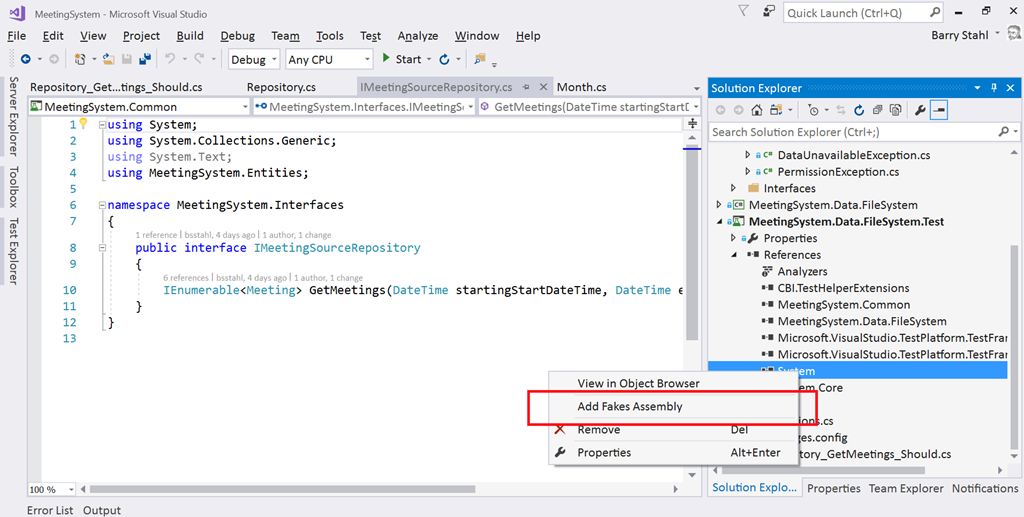

To use Shims, we first have to create a Fakes Assembly. This is done by right-clicking on the System reference in the test project from Visual Studio 2017, and selecting “Add Fakes Assembly” (full framework only – not yet available for .NET Core assemblies). Be sure to do this in the test project since we don’t want to actually deploy the Fakes assembly in our production code. Using the add fakes assembly menu item does 2 things:

- Adds a reference to Microsoft.QualityTools.Testing.Fakes assembly

- Creates 2 .fakes XML files in the Fakes folder within the test project. These items are built into corresponding fakes dll files that are deployed with the test project and used to provide stub and shim objects that mimic the objects in the selected assemblies. These fake objects reside in the same namespace as their “real” counterparts, except with “Fakes” on the end. Thus, our fake File object will reside in the System.IO.Fakes namespace.

The next step in using shims is to create a ShimsContext within a Using statement. Any method calls that execute within this context can be intercepted and replaced by our delegates. For example, a test that replaces the call to ReadAllText with a method that returns a single line of constant data can be seen below.

Methods on shim objects are referenced through properties of the fake object. These properties are of type FakesDelegate.Func and match the signature of the method being shimmed. The return data type is also appended to the property name so that each item’s signature can be represented with a different property name. In this case, the ReadAllText method of the File object is represented in the System.IO.Fakes.File object as a property called ReadAllTextString, of type FakesDelegate.Func<string, string>, since the method takes a string parameter (the path of the file), and returns a string (the text contents of the file). If we assign a method delegate to this property, that method will be executed in place of the call to System.IO.File.ReadAllText whenever ReadAllText is called within the ShimContext.

In the gist shown above, the variable p represents the input parameter and will hold the path specified in the test (in this case “April2017.abc”). The return value for our delegate method comes from the constant string dataFile. We can put anything we want here. We can replace the delegate with a call to an anonymous method, or with a call to an existing method. We can return a value gleaned from an external source, or, as is needed for our permissions test, throw an exception.

For the purposes of our test to verify that we throw a PermissionsException when a SecurityException is thrown, we can replace the value of the ReadAllTextString property with our delegate which throws the exception we need to test for, as seen here:

System.IO.Fakes.ShimFile.ReadAllTextString =

p => throw new System.Security.SecurityException("Test Exception");

Then, we can verify in our test that our custom exception is thrown. The full working example can be seen by grabbing the Master branch of the GitHub repo.

What can you test with these Shim objects that you were unable to test before? Tell me about it @bsstahl.

Tags: abstraction assembly code sample framework fakes interface moles mstest solid tdd testing unit testing visual studio

“One Reason to Change” Means the Code

Posted by bsstahl on 2015-07-06 and Filed Under: development

There was some confusion last week at the SoCalCodeCamp about what the phrase “One Reason to Change” actually means. As you probably know, the Single Responsibility Principle states that every class should have one and only one responsibility within the system. A common check for adherence to this principal is that the object has only one reason to change. However, it is important to realize that this is referring to the code (the class), not the state of the object (the instance). The state of the object may have many reasons to change, however, we as developers should have only 1 reason to change the code for our objects. For example, if the object is in the business-rules layer, we should only have to change the code if the business rules change. Likewise, if the object is in the data tier, it should only need code changes if the structure of the data changes.