The Critical C's of Microservices - Consistency

Posted by bsstahl on 2022-12-19 and Filed Under: development

"The Critical C's of Microservices" are a series of conversations that development teams should have around building event-driven or other microservice based architectures. These topics will help teams determine which architectural patterns are best for them, and assist in building their systems and processes in a reliable and supportable way.

The "Critical C's" are: Context, Consistency, Contract, Chaos, Competencies and Coalescence. Each of these topics will be covered in detail in this series of articles. Article 1 of the 6 was on the subject of Context. This is article 2 of the series, and covers the topic of Consistency.

Consistency

The world is eventually consistent. The sooner we get that through our heads and start expecting our systems to act like it, the fewer problems, we will have. In fact, I'll go out on a limb and say that most of the problems in building and maintaining microservice architectures are the result of failing to fully embrace eventual consistency from the start.

Data is consistent when it appears the same way when viewed from multiple perspectives. Our systems are said to be consistent when all of the data them is consistent. A system with strong consistency guarantees would be one where every actor, anywhere in the context of the application, would see the exact same value for any data element at any given time. A system that is eventually consistent is one with strong guarantees that the data will reach all intended targets, but much weaker guarantees about how long it might take to achieve data consistency.

Full consistency is impossible in a world where there is a finite speed of causation. Strong consistency can only be achieved when every portion of the application waits until the data is fully consistent before processing. This is generally quite difficult unless all of the data is housed in a single, ACID compliant data store, which of course, is a very bad idea when building scalable systems. Strong consistency, or anything more stringent than eventual consistency, may be appropriate under very specific circumstances when data stores are being geo-replicated (assuming the database server is designed for such a thing), but can cause real difficulties, especially in the areas of reliability and scalability, when attempted inside an application.

We should challenge demands for higher levels of consistency with rigor. Attempts to provide stronger consistency guarantees than eventual will cause far more problems than they are worth.

We will always need to look for situations where consistency problems might occur (i.e. race-conditions), expect them to happen, and try to design our systems in such a way as to not need to worry about them. Race conditions and other consistency problems are smells. If you are in a situation where you are might see these types of problems, it may indicate that you need to reevaluate the details of your implementation.

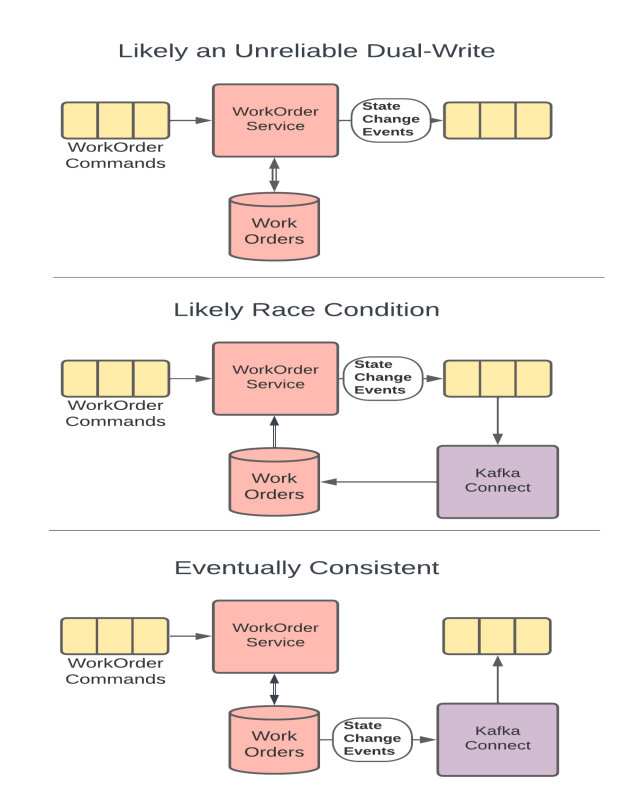

As an example, let's take a look at the 3 implementation diagrams below. In all 3 of these implementations, the goal is to have the WorkOrder service modify a WorkOrder and have the changes published onto a topic for downstream consumers. If a WorkOrder already exists, it needs to be loaded from the data store so that appropriate updates can be made. As you will see, the 3 implementations have very different reliability characteristics.

Implementation 1 - Dual-Write: In the 1st example, the WorkOrder service attempts to both update the entity in the database, and publish the changes to the topic for downstream consumers. This is probably an attempt to keep both the event and the update consistent with one another, and is often mistaken for the simplest solution. However, since it is impossible to make more than 1 reliable change at a time, the only way this implementation can guarantee reliability is if the 1st update is done in an idempotent way. If that is the case, in the circumstances where the 2nd update fails, the service can roll the command message back onto the original topic and try the entire change again. Notice however that this doesn't guarantee consistency at all. If the DB is updated first, it may be done well before the publication ever occurs, since a retry would end up causing the publication to occur on a later attempt. Attempting to be clever and use a DB transaction to maintain consistency actually makes the problem worse for reasons that are outside of the scope of this discussion. Only a distributed transaction across the database and topic would accomplish that, and would do so at the expense of system scalability.

Implementation 2 - Race Condition: In the 2nd example, the WorkOrder service reads data from the DB, and uses that to publish any needed updates to the topic. The topic is then used to feed the database, as well as any additional downstream consumers. While it might seem like the race-condition would be obvious here, it is not uncommon to miss this kind of systemic problem in a more complicated environment. It also can be tempting to build the system this way if the original implementation did not involve the DB. If we are adding the data store, we need to make sure data access happens prior to creating downstream events to avoid this kind of race condition. Stay vigilant for these types of scenarios and be willing to make the changes needed to protect the reliability of your system when requirements change.

Implementation 3 - Eventually Consistent: In the 3rd example, the DB is used directly by both the WorkOrder service, and as the source of changes to the topic. This scenario is reliable but only eventually consistent. That is, we know that both the DB and the topic will be updated since the WorkOrder service makes the DB update directly, and the reliable change feed from the DB instantiates a new execution context for the topic to be updated. This way, there is only a single change to system state made within each execution context, and we can know that they will happen reliably.

Another example of a consistency smell might be when end-users insist that their UI should not return after they update something in an app, until the data is guaranteed to be consistent. I don't blame users for making these requests. After all, we trained them that the way to be sure that a system is reliable is to hit refresh until they see the data. In this situation, assuming we can't talk the users out of it, our best path is to make the UI wait until our polling, or a notification mechanism, identifies that the data is now consistent. I think this is a pretty rude thing to do to our users, but if they insist on it, I can only advise them against it. I will not destroy the scalability of systems I design, and add complexity to these systems that the developers will need to maintain forever, by simulating consistency deeper inside the app. The internals of the application should be considered eventually consistent at all times and we need to get used to thinking about our systems in this way.

Goals of the Conversation

Development teams should have conversations around Consistency that are primarily focused around making certain that the system is assumed to be eventually consistency throughout. These conversations should include answering questions like:

- What patterns and tools will we use to create systems that support reliable, eventually consistent operations?

- How will we identify existing areas where higher-levels of consistency have been wedged-in and should be removed?

- How will we prevent future demands for higher-levels of consistency, either explicit or assumed, to creep in to our systems?

- How will we identify when there are unusual or unacceptable delays in the system reaching a consistent state?

- How will we communicate the status of the system and any delays in reaching a consistent state to the relevant stakeholders?

Next Up - Contract

In the next article of this series we will look at Contract and how we can leverage contracts to make our systems more reliable while still maintaining our agility.